The short answer is that it has both; it just depends how you use them.

This is a somewhat broad topic with lots of regional variation. Because I'm not sure where you are in your studies, I will answer with just an abbreviated outline that I hope will help you as an English speaker learning Portuguese.

Portuguese has both personal pronouns (like the word mine in English) and also personal determiners (like the word my in English). These look mostly alike but are used differently. Perhaps your confusion is because of how these look mostly alike in Portuguese, unlike in English where they can sometimes differ.

The determiners work a bit like adjectives in that they modify a substantive (noun) but are not substantives in and of themselves, so they cannot be the subject of a clause. They do have to agree with their noun.

So the personal pronoun doesn’t have a noun after it, but the personal determiner or personal adjective does. Sometimes these are called possessive pronouns and possessive determiners/adjectives instead of “personal” ones.

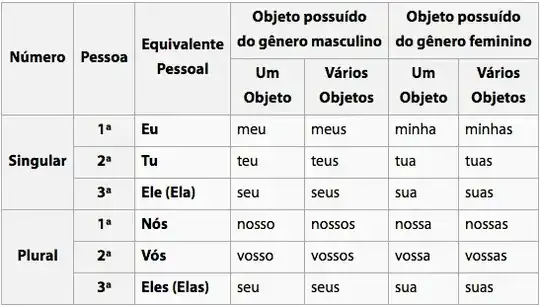

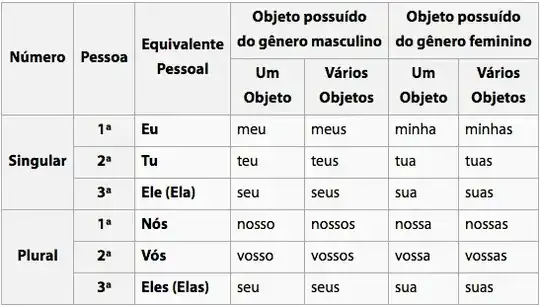

The basic paradigm is by person, number, and gender, from pt.wikibooks.org:

If you use those as possessive determiners, as in “(o) meu amigo” meaning “my (male) friend” or “(as) nossas amigas” meaning “my (female) friends”, the definite article is not obligatory. Brazilian speakers often omit it altogether.

However, when you use those words as possessive pronouns, you more commonly use the article, especially in Portugal. For example, “Tens o meu?” means “Do you have mine?” and “Viste as minhas?” means “Did you see mine?”

Here are just a few of the many ways these can trip you up:

The third person determiners, which come before the noun, are often replaced by the prepositional equivalent following it instead, especially in Brazil, so “o amigo dele” for example, not “o seu amigo”.

The second person tu forms are usually third person você forms in Brazil. This is a complicated topic in that it has even more regional variation than normal, so it would deserve its own question and answers for a fair treatment.

Almost no one outside of the far north of Portugal still uses the second

person vós forms save in old formulaic constructions like “vossa excelência”. See Pronomes de tratamento in Wikipedia. However, you should still learn these forms so that you are not surprised by them when reading literature.